Sarah Burton’s first runway for Givenchy had already betrayed signs of an over-manufactured sensibility, and her second confirms the slope: a couture of loud affirmation in the Chiuri vein, believing itself feminist simply because it exhibits. The clients, living trophies of this supposedly liberating fashion, paraded that evening in a pale yellow duchesse satin pea coat, cinched in black, as if to proclaim loudly and clearly their right to ostentation.

Sarah Burton’s first runway for Givenchy had already betrayed signs of an over-manufactured sensibility, and her second confirms the slope: a couture of loud affirmation in the Chiuri vein, believing itself feminist simply because it exhibits. The clients, living trophies of this supposedly liberating fashion, paraded that evening in a pale yellow duchesse satin pea coat, cinched in black, as if to proclaim loudly and clearly their right to ostentation.

We are told of the lightness of deconstructed jackets, now reduced to the limpness of a cardigan, as though stripping away all structure were synonymous with freeing women. Progress indeed! Erase poise to better expose. And that coat-dress of once majestic curves, now undone, its lapels ripped from the shoulders to let fall, miserably, the straps of a bra. Emancipation served up as freedom at any price, under the pretext of deconstruction.

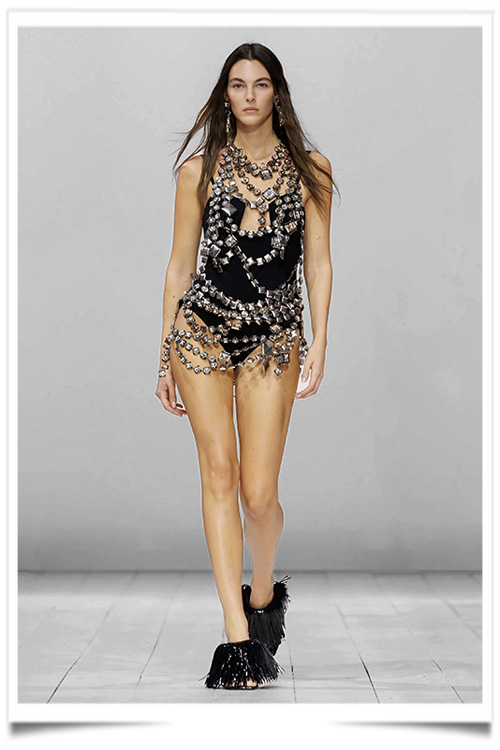

The full vocabulary is there: gaping collars, slanted jackets, hems hitched up, skirts dragged barely below the navel like a misfitted cloth fastened in haste. The body is no longer celebrated but turned into a noisy battleground of claims, a loud textile manifesto that mistakes provocation for power. Burton herself admits it: “the mind for business, the body for sin.” Thus the message of female power reduced to a shop-window slogan, Marilyn Monroe recycled in black-and-white motif to wrap a counterfeit ideology.

A white dress, like altar drapery torn from the silence of chambers, clutched by a model against a heaving chest bound in a peach corset; and that puff skirt bristling with feathers—were they not the chimerical dreams of a luxury consumed by itself? Then a camouflage-colored coat with almost bare shoulders, frayed like a tired curtain, or a bubble skirt bristling with fake plumes ripped from red muslin: one applauds the illusion, the “meticulousness” that contents itself with mimicking the feather, the luxury, while feigning fragility. And the audience cheers as if we ought to thank a designer for disguising attire as manifesto.

This collection is not a hymn to womanhood: it is a caricature of her strength, a couture of claim-making that confuses nudity with freedom and provocation with emancipation. Here, woman is not liberated: she is reduced to a banner. But when one observes, in the end, the rigidity she imposes upon her own body, the meaning becomes all the clearer.

FM