David Hockney is exhibiting at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and it must be said that everything is there: the large formats, the explosive colors, the small, very precisely calibrated dose of non-subversion, and above all, meticulous staging. But what do we really see? Hockney, certainly, but also a lot of Vuitton.

David Hockney is exhibiting at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and it must be said that everything is there: the large formats, the explosive colors, the small, very precisely calibrated dose of non-subversion, and above all, meticulous staging. But what do we really see? Hockney, certainly, but also a lot of Vuitton.

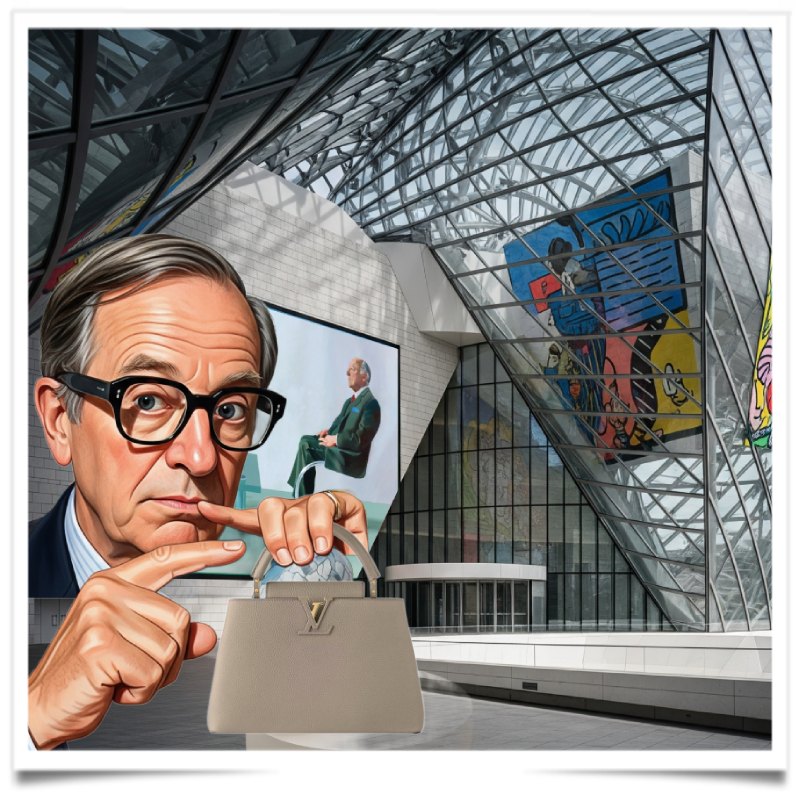

The Foundation, this contemporary luxury cathedral designed by Gehry, continues its balancing act between art and brand image. It sells us culture as one would sell a Capucines bag, with the veneer of storytelling and an impeccable display. Hockney, with his blond blow-dry and drawn cigarettes, ticks all the boxes: global star, mischievous octogenarian, and an artist “who still dares to use color” in a world saturated with digital gray. He’s perfect for the poster. A bit too perfect?

The exhibition journey is generous, immersive, visually very strong, and the use of a vibrant color palette, while charming to some, could be seen as a stagnant visual identity rather than a deep theoretical justification. But in striving to overwhelm us visually, the exhibition ultimately resembles a kind of Arty Disneyland: everything is big, everything is “bigger,” and above all, everything is “Hockneyland.”

But who holds the reins of this visual amusement park? Hockney himself, of course, but also supervised and assisted by his partner and his loyal studio manager. And then there’s that famous censored poster, where the artist depicts himself with a cigarette. Provocation? A wink? Soft rebellion? At 88, Hockney still plays the punk, but a punk perfectly compatible with the communication of a luxury group. It’s transgressive, but just enough for the group.

Let’s not be unfair; his paintings continue to manipulate perspective like a magician, twisting vanishing lines, splashing the canvas with acid green and improbable pinks. There’s breadth, certainly sincerity, sometimes even unexpected emotion, especially in the winter landscapes or the large melancholic panoramas.

But here again, the message is enveloped, framed, filtered. Hockney speaks of death, solitude, the passing of time… but all of this comes across like a pretty postcard. We admire, we photograph, we leave with the feeling of having “seen something,” without really knowing what.

It’s beautiful, it’s clean, it’s luxurious, but perhaps a bit too much. Hockney still has things to say, but in this “Vuitton-ized” temple of art-as-spectacle, his voice seems drowned out by the background noise of branding. However, in the lord’s private collection, there is a small Hockney, which probably explains this prominence.

FM