The luxury sector is going through an unprecedented period of turbulence. Long a symbol of excellence, abundance and aspiration, it is now undergoing a tangible erosion, illustrated by the upheaval of historic department stores. In the United States, Saks Global has just announced the elimination of 500 to 600 brands from its portfolio – a strong gesture that reflects a brutal readjustment in the face of a reality that is less golden than it used to be.

The luxury sector is going through an unprecedented period of turbulence. Long a symbol of excellence, abundance and aspiration, it is now undergoing a tangible erosion, illustrated by the upheaval of historic department stores. In the United States, Saks Global has just announced the elimination of 500 to 600 brands from its portfolio – a strong gesture that reflects a brutal readjustment in the face of a reality that is less golden than it used to be.

Richard Baker, Executive Chairman of Saks Global, has publicly acknowledged that the current model has become unsustainable. With 2,660 suppliers, the machine had run out of steam, accumulating unprofitable or misaligned partnerships. This drastic rationalisation reflects a profound change: the end of an era of opulence without strategy, when the accumulation of brand names took precedence over the coherence of the offer.

The shift towards ‘controlled brands’ and more controlled joint ventures such as Authentic Luxury Group clearly demonstrates a desire to regain control in the face of a fragmented, uncertain market, saturated with products that no longer find takers. The ambition to reposition brands such as Barneys New York and Hervé Léger through hybrid concepts (retail, entertainment, hospitality) speaks volumes about the need to reinvent themselves, if they cannot continue to sell the pure dream.

In Europe, the situation is hardly any better. La Samaritaine, the Parisian landmark resurrected by LVMH after 16 years of closure, is struggling to find its place. Its ultra-premium offering, its aisles deserted by tourists and its elitist positioning all call into question its long-term viability. Luxury is no longer as popular as it used to be, at least not in these historic temples where operating costs are soaring and the younger generation no longer recognises itself.

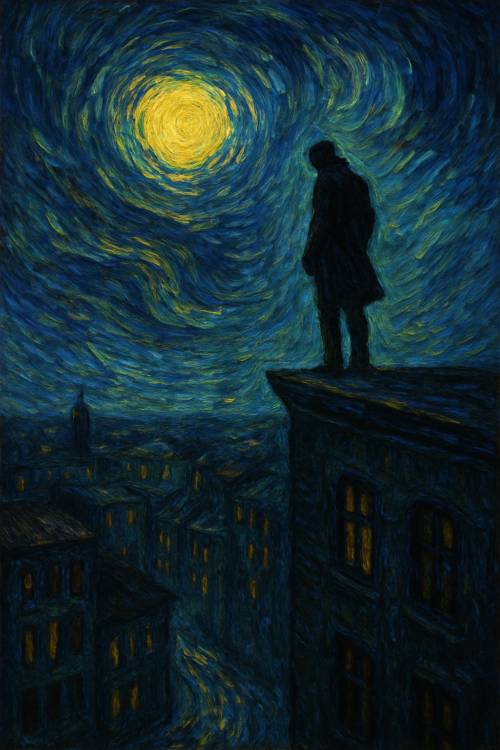

These warning signs are all converging: luxury, as it has been shaped over the last few decades – ostentatious, massive, expansive is reaching its limits. The global market is slowing down, and consumers are becoming more selective, more volatile, and sometimes even indifferent. Prestige alone is no longer enough.

The fall of luxury is not a sudden collapse, but a slow metamorphosis. And department stores, once showcases of splendour, are the first witnesses.

FM